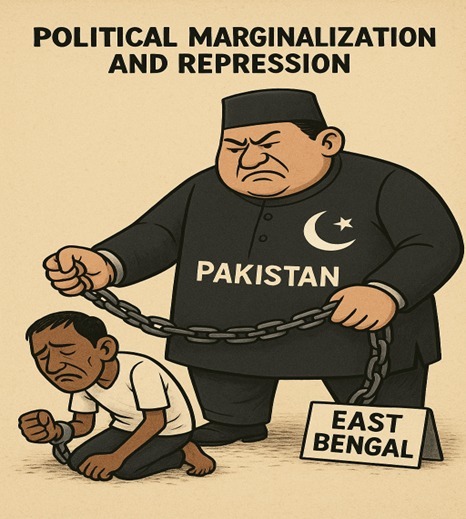

The history of Pakistan’s treatment of East Bengal—later renamed East Pakistan—is not merely a case of administrative reorganisation. It represents a deliberate cultural onslaught designed to erase Bengali identity, marginalise its language, and silence its people. The renaming from East Bengal to East Pakistan was not an act of bureaucratic neutrality; it was a political move that formed part of a wider pattern of cultural subjugation, one that ultimately erupted in the violence of the 1952 Language Movement.

Following the Partition of British India in 1947, Pakistan emerged as a state divided by over 1,600 kilometres of Indian territory, uniting two regions that shared religion but little else. East Bengal, geographically separated yet demographically dominant, quickly found itself subordinated to the political and cultural will of the western provinces. Tensions surfaced almost immediately. In 1948, Pakistan’s leadership declared Urdu—the language of a small elite concentrated in the west—as the sole national language. Bengali, though spoken by more than half the population, was excluded from the national identity framework. This decision was not about communication but about control. Language became a tool of hierarchy, reinforcing the dominance of West Pakistani elites while consigning Bengalis to the margins of national life.

The move to rename East Bengal as East Pakistan in 1955 under the “One Unit” scheme deepened this process of erasure. The word “Bengal,” steeped in cultural, literary, and historical significance, disappeared from official usage. In its place came a homogenised, centralised identity that denied the distinctiveness of Bengali civilisation. This was an attempt to impose uniformity upon a nation defined by diversity—a calculated effort to dissolve regional pride in favour of a contrived Pakistani nationalism anchored in the west.

The reaction of the people of East Bengal to this sustained marginalisation was one of defiance. The spark came in 1952, when Prime Minister Khwaja Nazimuddin reaffirmed that Urdu would remain the only state language of Pakistan. The announcement provoked widespread anger in East Bengal, where the language question had become synonymous with dignity and survival. In a desperate attempt to stifle dissent, the government imposed Section 144, banning public meetings and processions. But on 21 February 1952, students from Dhaka University and other institutions took to the streets in peaceful protest. What followed would leave an indelible scar on the national memory. Police opened fire on unarmed demonstrators near Dhaka University and the East Pakistan Legislative Assembly, killing several students, including Rafiq Uddin Ahmed, Abul Barkat, Abdul Jabbar, Abdus Salam, and later Shafiur Rahman. The exact death toll remains disputed, with some reports citing seven and others suggesting more, but the symbolism of the bloodshed was unmistakable. The Pakistani state had declared war on its own majority.

The events of 1952 transformed a linguistic dispute into a political awakening. The Bengali language became a banner of resistance, uniting people across class and creed in defence of their identity. The state’s attempts at control extended far beyond language. In education, Bengali literature and instruction were systematically undermined as Urdu-centric policies reshaped curricula and public institutions. In administration, Bengalis remained grossly underrepresented in the civil service, military, and higher offices of state, despite constituting the majority of the population. The imbalance reinforced the perception that East Pakistan was a colony of the west, exploited economically and humiliated culturally.

Cultural suppression took on more insidious forms as well. Some Pakistani officials disparaged Bengali as a “Hindu language” and proposed altering its script to Arabic in a misguided attempt to align it with Islamic identity. Such ideas, though never formalised, reflected the regime’s desire to strip Bengali of its secular, syncretic heritage and to sever its connection with centuries of literature, poetry, and intellectual tradition. Every institution—from schools to currency to postage stamps—became a battleground over representation, where Bengali identity was systematically diminished.

The 1952 Language Movement became the turning point in this struggle. It was not merely a protest over words; it was an assertion of existence. The deaths of the student martyrs galvanised an entire generation and transformed cultural defiance into political consciousness. In 1956, under mounting pressure, the government was finally forced to recognise Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan. The concession, however, came too late to repair the fractures within the nation. The movement had already planted the seeds of nationalism, which later blossomed into the Six-Point Movement for autonomy and ultimately the Liberation War of 1971.

The legacy of the movement endures far beyond Bangladesh’s borders. The martyrs of 1952 are commemorated each year on 21 February, observed in Bangladesh as Shaheed Dibosh (Martyrs’ Day). In 1999, UNESCO declared this date as International Mother Language Day, recognising the universal right to linguistic and cultural identity. What began as a regional protest became a global symbol of resistance against cultural domination.

The renaming of East Bengal to East Pakistan was thus never an administrative footnote. It was an act of symbolic violence, a calculated attempt to erase a people’s history from the map and replace it with an imposed identity. When the state dictates how its citizens speak, think, or remember, it seeks not just obedience but ownership of their very sense of self. The events of 1952 exposed the moral bankruptcy of that project.

In trying to suppress the Bengali language, Pakistan’s rulers sought to silence an entire civilisation—but their actions had the opposite effect. From the blood of the students of Dhaka was born a nation whose very existence stands as a rebuke to cultural tyranny. The struggle for linguistic recognition in East Bengal was, in truth, the first declaration of Bangladesh’s independence. It remains a reminder that when language is attacked, identity itself bleeds—and that the resilience of a people’s voice can outlive the empires that try to silence it.