Bangladesh’s current turmoil is usually explained as politics in motion — leadership change, rival factions, old scores being settled. That explanation is convenient, but incomplete. What the country is facing today looks less like a temporary political storm and more like the result of long-term institutional weakening, where accountability has steadily thinned out and violence has filled the vacuum.

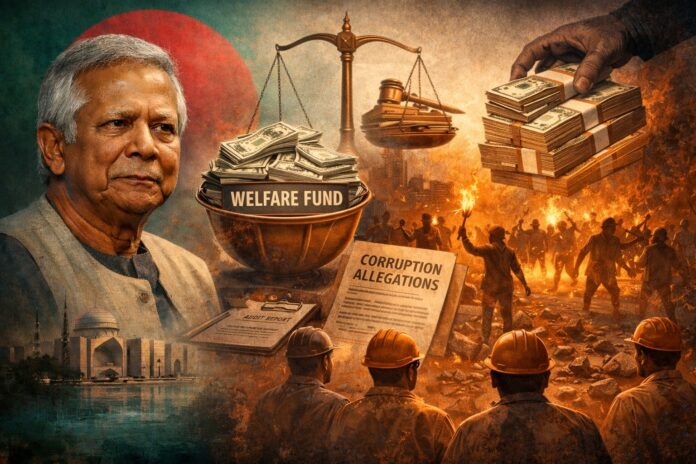

Seen through that lens, the Grameen Telecom welfare fund case involving Muhammad Yunus is no longer just a matter for the courts. It has come to symbolise something larger: how governance failures at the top quietly corrode order on the ground, until disorder begins to feel normal.

A Law That Leaves Little Room for Interpretation

The legal issue itself is straightforward. Bangladesh’s labour framework requires companies to set aside a portion of profits for employee welfare. This money is not optional. It is not flexible. It is meant to sit outside management control and be used solely for workers’ benefit.

Prosecutors allege that around Tk 25 crore collected under this provision at Grameen Telecom was transferred into accounts effectively controlled by management, without workers’ consent. Yunus, a former chairman of the company, has denied wrongdoing and called the case harassment. The matter is before the judiciary, and as a matter of law, he remains innocent unless proven otherwise. But the importance of the case does not depend on how the verdict eventually turns out.

When Reputation Becomes a Substitute for Oversight

For decades, Yunus has occupied a rare space in public life. His work in microfinance earned global admiration, and his institutions were often viewed less as conventional corporate entities and more as moral projects. That distinction mattered. It softened scrutiny and created a degree of deference that few organisations enjoy.

This is not unique to Bangladesh. Around the world, socially branded institutions often benefit from trust that goes beyond formal compliance. The risk, however, is obvious. When reputation begins to replace oversight, legal boundaries start to blur. Welfare funds exist precisely to prevent that — to ensure workers’ rights do not depend on managerial goodwill. Any uncertainty about how such funds are handled strikes directly at the credibility of the system.

Why This Matters in a Violent Moment

Bangladesh is currently seeing a worrying rise in mob attacks, targeted killings, assaults on journalists, and intimidation of minority communities. These incidents are often discussed as isolated law-and-order failures. They are not.

Violence takes root when people stop believing that rules are applied evenly. When citizens feel that influence and stature matter more than legality, the authority of the state weakens. In that space, rumours become weapons, mobs become judges, and force replaces process.

This is where the welfare fund case intersects with the wider crisis. Fair or not, it reinforces a public perception that powerful institutions operate by different rules. That perception alone is enough to undermine trust — and trust is the thin line that keeps societies from sliding into chaos.

The Workers’ Question Is the Most Damaging One

The most telling voices in this story are not political. They belong to workers quoted in Bangladeshi media who said they were unaware of the scale of funds accumulated in their name and saw little direct benefit from them. Their concern is not ideological. It is practical and deeply personal.

When workers lose faith in the protections promised by law, that distrust does not stay confined to the workplace. It spreads outward — to labour law, to corporate governance, and eventually to the state itself. In an already tense environment, that erosion of confidence is dangerous.

Why the Region Is Watching

Bangladesh’s instability does not stop at its borders. Weak governance creates openings — for radical groups, organised crime, and cross-border spillovers. For India and the wider region, the breakdown of rule-based order in Bangladesh is not an abstract concern. It carries real security implications.

This is why cases like this matter. Not because of who is on trial, but because of what they signal. A state that struggles to enforce labour protections against elite institutions will struggle even more to impose order on the streets.

Law or Influence — A Choice That Cannot Be Deferred

The Yunus case does not erase past contributions, nor does it establish guilt. That judgment belongs to the courts. But it has already forced an unavoidable question into public debate: does law still outweigh reputation?

Bangladesh is approaching a point where that question can no longer be postponed. Either accountability becomes visible and consistent — regardless of status — or violence, intimidation, and informal power will continue to set the terms of public life.

The welfare fund case is not a distraction from the country’s unrest. It is part of the same story. And the public, watching events unfold, is asking a question that cuts through politics entirely: if laws cannot reliably protect workers’ money, can they protect anyone at all?